What are we Taking?

A snapshot of our shared altered reality

Mention “England” and “drugs” in the same sentence and, depending on who you’re writing for, old tropes can get tossed out like an empty Elf bar: from deviant teenage devils honking balloons in municipal car parks to pranging street zombies puffing spice in doorways.

If you’re subscribed to this Substack, you’ll probably take a more nuanced view. You’ll also likely be across the presence of nitazenes – a synthetic opioid analogue anywhere between 50 to 500 times stronger than heroin – in the drug supply and, of course, ketamine’s ascent to the media drug du jour. (To be fair: there has been a twelve-fold increase in new referrals to treatment in a decade.)

Drug-related fatalities have been scaling new heights: in 2024 there were 5,565 deaths registered in England and Wales, with opioids involved in nearly half of them. Coke/crack fatalities are 11 times higher than in 2011. These numbers also don’t take into account recent King’s College research that found official opioid and cocaine deaths were vastly undercounted. Men continue to outnumber women, and the highest death rate remains among people born in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

The majority of these deaths, tragic as each one is, happen within a relatively small portion of the drug-using population. So what substances are the rest of England and Wales taking?

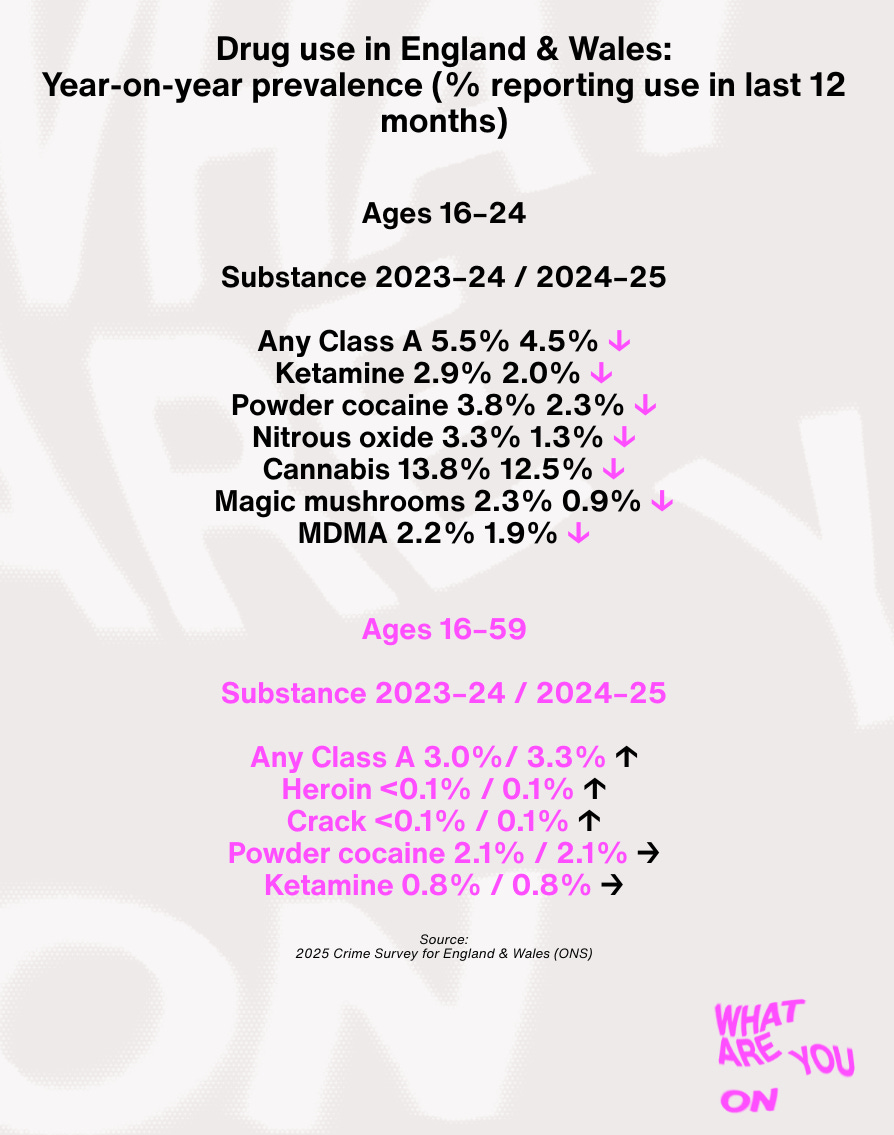

The annual drugs misuse stats – whilst flawed – offer an end-of-year insight into how the country is choosing to alter its reality. I obviously wouldn’t expect a normal person to go and read the appendix tables, so here’s a précis of what I’m optimistically calling “the best bits”.

These numbers appear to reflect a post-Covid generation of young people turning somewhat away from intoxicants and, seemingly, from going out in general with 28% of late-night venues shutting since lockdown. There’s also the resilience of the older drug-taking crowd which – given the atrocious state of our country’s finances, public services, and communal mental health – seems pretty logical.

It’s worth noting that a prevalence of ~0.0% for drugs like heroin and crack doesn’t literally mean none – it means the proportion was too small to register reliably in the survey. And that rising to 0.1% only meant an increase of 14,000 people and 11.000 people (heroin and crack respectively).

Plus, as we’ll get to, these statistics aren’t definitive and don’t take into account the homeless population, where many of those users will reside.

To delve further into the data, I called up Harry Sumnall. He is a Professor in Substance Use at the Public Health Institute, Liverpool John Moores University, and sits on the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD), which advises the government on drug policy. There’s no one better placed to guide us through their nooks and nuances.

WAYO: Hey Harry. Use of most substances dropped in the younger cohort – but stayed the same in the older. Can we view this as a broad generational segue towards a more sober lifestyle?

HS: It does appear to be heading in that direction. But, while it’s important to look at year-to-year changes, there can also be what we call “noise” [anomalies] in the data. So it’s important to look at trends — by that we mean across five, 10, 20 years. With the 16-to-24 group, there has been this decline [in drug use] since a peak in the late 1990s.

That’s the overall trend, but there might be individual drugs that buck within that – we previously saw a rapid rise in last-year cocaine use amongst older and younger users, for instance. But powder cocaine seems to have reduced, and MDMA continues to fall out of fashion.

Ketamine has been getting all the attention this year, but there’s been a significant drop in younger people.

It seems to be the drug that everyone is concerned about. Prevalence [use] rates were 2.8% in the younger age group: about one in 25 people. This year that has declined to around 2%. These are small numbers, but that’s quite a sharp reduction. Alongside that, there’s been a sharp increase in treatment presentations for ketamine, despite prevalence going down.

Is this representative of a smaller cohort still using to excess but fewer recreational users, perhaps encouraged by increased awareness of harms?

We don’t really know, but I’m sure that has something to do with it. The principle is that around 20% of people who engage in drug use consume about 80% of the products. There are often comorbidities involved: mental health or developmental challenges, housing issues, and so forth.

The number of young people using nitrous oxide has reduced a lot. How much can we attribute this to 2023’s change in legislation [nitrous was reclassified as a Class C drug, making possession illegal]?

There haven’t been any studies yet, and we saw post-Covid that there was already a decline. I think we had already hit peak nitrous oxide, with changes in socialisation practices and drug fashions. So it was probably always going to decline.

But I also think – and this is just my expert opinion – that reclassification has made a difference, particularly in terms of open selling, bulk sales, and high-quantity canisters online. It was so readily available. If someone still wants to get hold of it, they can, but the levels have changed quite dramatically. We often think drug laws don’t have any impact, but a major driver of nitrous oxide use was its online availability. Driving that down appears to have reduced use.

I’m broadly pro-regulation (certainly decriminalisation) of drugs, but the nitrous law appears to have had a positive effect. Is that fair?

If you’re a legislator, you’d say this has been a success: numbers have dropped, it’s harder to buy online, and perhaps we’re seeing fewer serious neurological health outcomes. But the unintended consequence is that there will always be a demand for intoxication. So what replaces nitrous? There’s an argument it’s been replaced by ketamine to some extent. Or it may be that people who use drugs riskily used other substances in risky ways.

How should we view the mooted reclassification of ketamine [from Class B to Class C]?

I sit on the ACMD so I can’t talk particularly about recommendations. But my view has been that, if we’re interested in reducing harm from ketamine, it’s less of a supply issue than with nitrous oxide. You have fewer policy tools with a drug on the illicit market. Reclassification might have a part to play but it’s going to be about public health approaches: ensuring adequate early intervention. Clear pathways between primary and secondary care so that users don’t feel stigmatised. Ensuring services know what to do about ketamine problems.

Psychedelics appear to have declined after a supposed “boom” during lockdown – especially among younger people.

It’s hard to know what’s happening with psychedelics. There’s been lots of attention: treatment, retreats, microdosing. Perhaps they became normalised for certain functions, and some of that attention has now shifted toward clinical development. Anecdotally, there seems to be less discussion of wider psychedelic culture. But psychedelics have always moved in cycles. We’ve seen it since the 1960s. It doesn’t surprise me.

In terms of cocaine: there’s quite a high drop for young people, continuing a gradual decline. But the older cohort has stayed in the same bracket [between 2.9% and 2.1%]

since 2010.

Yeah, it peaked around 2009 and the interesting thing is to look at demand and supply. It’s never been more available and affordable. Yet prevalence of use, especially in young adults in England and Wales, is receding.

So something else is happening at a national level in regards to the appeal of cocaine?

That might relate to harm concerns, how young people socialise, it could be replaced by other drugs or replaced by no drugs at all. But I think it’s a good indication of how broader social and cultural forces can drive waves of drug use over and above important international factors.

The small increase in crack and heroin – should we read anything into that?

Where increases are under 0.5%, this survey isn’t well suited to detecting meaningful change.

A recent King’s College study suggested opioid and cocaine deaths are undercounted. How reliable are these stats?

It’s a crime survey, not just a drug survey – so people are asked in a wider survey about their experiences of crime. A proportion are then asked the drugs module. It’s also for households and thus doesn’t capture people who aren’t in them – like prisoners, homeless people, students living in halls – so there’s underestimates there.

Do people from the ONS literally come around knocking for you to take it?

You’ll have a letter from the ONS. Once you register your interest, someone will come around with an iPad or tablet. They will ask questions then, for the drugs module, will hand the tablet over for you to answer.

This must drive underreporting?

Certainly. If you look at other drug surveys in the UK, they tend to record higher levels of use. These methodological concerns are well-known and transparent but the government stats are useful for the trends though.

Is there anything to suggest drug deaths will fall in the short to medium term?

Looking at characteristics of drug–related deaths, they tend to be focused on particular substances and individuals – quite high-risk and vulnerable cohorts.

It’s somewhat macabre to say, but an epidemiological reality, that I think the only way these drug deaths will fall is when those people at higher risk have died. Whether that’s through drug-related deaths, long term conditions or other causes.

I don’t necessarily think those amongst this cohort will die anytime soon. But what might be encouraging is, and this is again somewhat macabre, is the average age of drug-related deaths is increasing: what we call the birth cohort effect. There does’t appear to be the same increase in deaths in the younger cohort – those that are 18, 19 or 20 years-old now. It’s not going to happen for quite a while though.

Okay. Thanks for chatting, Harry

These are some excellent drugs-related charities trying to change the game

Transform Drug Policy Foundation

Release Drugs

Cranstoun

ChangeGrowLive

The Loop

SafeCourse